The Daily Yomiuri reports today on some new inventions intended to invade your privacy, er, help the kids of the elderly make sure they are okay. (The article is bylined "The Yomiuri Shimbun", which I often suspect means they are cribbing from press releases.)

The first one is an electric hot water maker for tea (a "potto", or hot pot) from Zojirushi (the biggest hot pot maker). The i-Pot is the first product in their "Mimamori" ("keeping an eye out") service. (Website is here, but Japanese only; a few photos are here.) It has a built-in DoCoMo DoPa packet radio transceiver, and sends email twice a day to a designated list of recipients with the recent usage records, or you can poll it to find out the latest. The pot is 5,250 yen (about $50), then the service is 3,150 ($30) a month. They claim to have more than 2,500 customers already.

I've never seen my mother-in-law drink water; she drinks tea continuously. But what if yours doesn't? Not to worry, ArtData can attach sensors to everything from your refrigerator door to the toilet floor mat to check up on you. Paramount Bed Co. makes an adjustable (hospital-style) bed that will report the height and tilt of the bed via some sort of wireless, and Yozan has a gadget based on a two-way pager that the city government of Wako, Saitama Prefecture is deploying. A local government official sends you a message each morning, and you respond by pressing one of the three buttons, "well", "not well", or "call me".

The privacy implications are not going unnoticed, but Japan is most decidedly coming down on the side of more information. Helping the community take better care of the rapidly aging population here is seen as the principal imperative.

Monday, November 28, 2005

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Stop Me If You've Heard This One Before...

Found via these four physics blogs, a Register article saying that Maxell will be offering holographic storage developed by InPhase Technologies by late 2006. 300GB, 20MB/sec. (what's the access time?), roadmap to 1.6TB/disk.

Creating a new, removable, random-access, high-performance storage medium is really hard. For optical things, the readers/writers tend to be expensive; to amortize that cost and get competitive GB/$, you want to make it removable, which means you have to lock in a data format for years, which hurts your density growth (while fixed magnetic disks are growing at 60-100%/year), makes more complex mechanics, makes it harder to keep the head on track, and makes serious demands on interoperability of readers and writers. The heavier optical heads make fast seek times problematic, too.

Good luck to them. I hope they have better luck than ASACA (where I'm proud to say I worked on just such a difficult project; I'm sad to say it failed, but the company still does well with autochangers for many media types), Terastor (whose website claims $100M in development generated 90 patents; too bad no successful drives/media came out), Quinta (now completely gone, as far as I can tell; absorbed back into Seagate?), Holoplex (gone), Tamarack (gone?), and a host of others did on high-speed magneto-optical, near-field magneto-optical, and holographic storage media.

I can only think of five successful removable, rotating media types: three sizes of floppy disk, CDs, and DVDs. You might throw in the first MO (600MB) and one or two types of removable hard disk, if you're generous. The newer optical media require long lead time, large corporate consortia, and enormous standards, marketing, and manufacturing efforts.

Will this finally be holographic storage's breakthrough? Stay tuned...

[Update: Sam Coleman, one of the gods of supercomputer mass storage and hierarchical mass storage, says he first saw holographic storage in 1979, and delivery was promised in eighteen months. Sam found this page with a little such history on it.]

Creating a new, removable, random-access, high-performance storage medium is really hard. For optical things, the readers/writers tend to be expensive; to amortize that cost and get competitive GB/$, you want to make it removable, which means you have to lock in a data format for years, which hurts your density growth (while fixed magnetic disks are growing at 60-100%/year), makes more complex mechanics, makes it harder to keep the head on track, and makes serious demands on interoperability of readers and writers. The heavier optical heads make fast seek times problematic, too.

Good luck to them. I hope they have better luck than ASACA (where I'm proud to say I worked on just such a difficult project; I'm sad to say it failed, but the company still does well with autochangers for many media types), Terastor (whose website claims $100M in development generated 90 patents; too bad no successful drives/media came out), Quinta (now completely gone, as far as I can tell; absorbed back into Seagate?), Holoplex (gone), Tamarack (gone?), and a host of others did on high-speed magneto-optical, near-field magneto-optical, and holographic storage media.

I can only think of five successful removable, rotating media types: three sizes of floppy disk, CDs, and DVDs. You might throw in the first MO (600MB) and one or two types of removable hard disk, if you're generous. The newer optical media require long lead time, large corporate consortia, and enormous standards, marketing, and manufacturing efforts.

Will this finally be holographic storage's breakthrough? Stay tuned...

[Update: Sam Coleman, one of the gods of supercomputer mass storage and hierarchical mass storage, says he first saw holographic storage in 1979, and delivery was promised in eighteen months. Sam found this page with a little such history on it.]

A Visit to an Asteroid

I don't know if this is making much news elsewhere, but the Japanese probe Hayabusa touched down on the asteroid Itokawa on Saturday, and is believed to have retrieved soil samples which it will hopefully return to Earth next June.

This is the first landing on a body other than the Moon, Mars, and Venus [note: that's what their press release said, but they've apparently forgotten about Cassini-Huygens' landing on Titan], and the first by a country other than the U.S. or U.S.S.R./Russia. If the sample return succeeds, it will be the first sample return (by anyone) from beyond the Moon's orbit, too. The probe uses an ion engine, which is very advanced technology, and had to navigate and land autonomously due to the distances involved, which is impressive. It hasn't all been smooth; this was the second landing/sample retrieval attempt, and a secondary probe failed to land, as well.

Itokawa is a fascinating asteroid; it has no craters. It looks a little like Joshua Tree, with lots of rocks sticking up out of a dusty plain.

A somewhat broken English news release is here, better pictures on the Japanese page here, current status (English) here, and the English project home page here.

This is the first landing on a body other than the Moon, Mars, and Venus [note: that's what their press release said, but they've apparently forgotten about Cassini-Huygens' landing on Titan], and the first by a country other than the U.S. or U.S.S.R./Russia. If the sample return succeeds, it will be the first sample return (by anyone) from beyond the Moon's orbit, too. The probe uses an ion engine, which is very advanced technology, and had to navigate and land autonomously due to the distances involved, which is impressive. It hasn't all been smooth; this was the second landing/sample retrieval attempt, and a secondary probe failed to land, as well.

Itokawa is a fascinating asteroid; it has no craters. It looks a little like Joshua Tree, with lots of rocks sticking up out of a dusty plain.

A somewhat broken English news release is here, better pictures on the Japanese page here, current status (English) here, and the English project home page here.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Ion Trap Quantum Computer Architecture

With the deadline for the 2006 conference in a week, it seems like a good time to talk about the International Symposium on Computer Architecture. ISCA is the premiere forum for architecture research; it's very competitive and papers there are, as a rule, highly cited.

Mark Oskin's group published a good ion trap system architecture paper in ISCA 2005. The paper "An Evaluation Framework and Instruction Set Architecture for Ion-Trap based Quantum Micro-architectures" shows how to take the technology designed by the Wineland group at NIST and begin designing a complete computer out of it. They evaluate different choices of layout: how many traps per segment of wire, how to minimize the number of turns an ion must make, etc. They also discuss their tool chain for doing much of the work.

When we systems folk (there are only a handful of us in quantum computing, with Mark leading the class) talk about architecture, this is the kind of thing we mean. This work suggests that most of the decoherence in an ion trap system will come from turning corners, and therefore the research they are doing has the potential to have a dramatic effect on the practical threshold necessary for QEC to be effective.

[Disclaimer: Mark and I have a joint paper under consideration, though I had nothing to do with the work described here.]

Mark Oskin's group published a good ion trap system architecture paper in ISCA 2005. The paper "An Evaluation Framework and Instruction Set Architecture for Ion-Trap based Quantum Micro-architectures" shows how to take the technology designed by the Wineland group at NIST and begin designing a complete computer out of it. They evaluate different choices of layout: how many traps per segment of wire, how to minimize the number of turns an ion must make, etc. They also discuss their tool chain for doing much of the work.

When we systems folk (there are only a handful of us in quantum computing, with Mark leading the class) talk about architecture, this is the kind of thing we mean. This work suggests that most of the decoherence in an ion trap system will come from turning corners, and therefore the research they are doing has the potential to have a dramatic effect on the practical threshold necessary for QEC to be effective.

[Disclaimer: Mark and I have a joint paper under consideration, though I had nothing to do with the work described here.]

Friday, November 25, 2005

Music Review: Tatopani at Sweet Basil

Double disclaimer: number one, Robbie Belgrade is a friend of mine, number two, the music of Tatopani is exactly the kind of music I like :-). So, your mileage may vary.

Last night Mayumi and I snuck out to hear Tatopani play at Sweet Basil in Roppongi. They were playing a (sold out!) release party for their new CD, Azure (which has been reviewed by Daily Yomiuri, Mainichi, and Japan Times, so if you don't trust my review, try them).

I have heard Robbie play with a couple of other groups; I like this one the best, by far. Tatopani is Robbie, Chris Hardy, and Andy Bevan, with the new addition of Bruce Stark, all of whom have lived in Tokyo for a long time.

So what's the music? One of them described Tatopani as "kick-ass world music" in an interview. That's as good a description as any I could come up with; I don't have the technical vocabulary to explain it. If you like, say, Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road albums, recent Wayne Shorter, and Dave Brubek's "Blue Rondo a la Turk", you're going to like Tatopani. This is not the "world pop" of somebody like Angelique Kidjo, nor the driving rock-influenced work of Joe Zawinul. The rhythms are complex, but there is a lot of space in the music, and indeed they name Miles Davis' "Bitches Brew" as an influence.

All of the guys play an array of instruments. Robbie's preferred woodwind axe is a bass clarinet, but I might actually like his sax playing better. For good measure, he plays a very mean tabla, and a pandeira (Brazilian tambourine) that has remarkable expressiveness. Chris's percussion setup looks like he went into a percussion store and bought one of everything. He had seven gongs, eleven cymbals, a djembe, another African drum (ashiko, maybe?), a wooden box, a doumbek with a high, crisp sound, and on and on. On one tune, he played a terracotta vase which had a nice bass and a higher, clear sustain. Andy played soprano sax, didjeridoo, flute, and some percussion. He played a kalimba (African alto music box played with your thumbs, more or less) on one very nice tune, "El Jinete". Bruce is the slacker in the instrument count department; he stuck with acoustic and electric pianos, except for one tune he contributed some percussion to.

Most of the tunes on Azure were written by Robbie. Some start with a spacious, slow opening before moving into more up-tempo sections. I really like the bass groove Bruce lays down on the opening track, "Azure". As you'd expect with a group like this, the rhythms are hideously complex in places; one tune is in 11/4 time (named, not coincidentally, "Eleven"), and I couldn't identify the time signatures on a couple. They opened their second set with "Bat Dance", by Chris, in which Robbie and Andy support a long, complex, exciting solo by Chris on the frame drum. The range of sounds ten fingers can get out of a piece of skin stretched across a wide, shallow wooden frame is simply amazing.

Sweet Basil is a great place to hear music. It's new, the food and sound are quite good, and the ventilation keeps the smoke level down. The desserts were excellent, and the potato soup rich. Mayumi had duck and I had lamb for main dishes; they needed a little salt and pepper, but were well prepared and presented. If you're headed there, make reservations, and show up early. Seating is by order of arrival. Tatopani sold out; I would guess the place probably holds 2-300 people. We got there early enough for good, but not great, seats, about 7:00.

The web site only lists last night's gig, but they were talking about a number of other appearances scheduled around Japan in the next several months. Hopefully they'll post a schedule soon. I know Chris is playing a percussion duo concert with, um, I'm having trouble reading the name, Shoko Aratani? at Philia Hall on March 4.

Hmm, Chris and Shoko are also playing with Eitetsu Hayashi on December 23rd? Hayashi is the taiko player of whom another professional musician said, "When Eitetsu plays, times stops and you can hear the Universe breathe." He's astonishing. See this if you can!

Tatopani's CDs can be ordered through their web site, where you'll also find sound samples.

Last night Mayumi and I snuck out to hear Tatopani play at Sweet Basil in Roppongi. They were playing a (sold out!) release party for their new CD, Azure (which has been reviewed by Daily Yomiuri, Mainichi, and Japan Times, so if you don't trust my review, try them).

I have heard Robbie play with a couple of other groups; I like this one the best, by far. Tatopani is Robbie, Chris Hardy, and Andy Bevan, with the new addition of Bruce Stark, all of whom have lived in Tokyo for a long time.

So what's the music? One of them described Tatopani as "kick-ass world music" in an interview. That's as good a description as any I could come up with; I don't have the technical vocabulary to explain it. If you like, say, Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road albums, recent Wayne Shorter, and Dave Brubek's "Blue Rondo a la Turk", you're going to like Tatopani. This is not the "world pop" of somebody like Angelique Kidjo, nor the driving rock-influenced work of Joe Zawinul. The rhythms are complex, but there is a lot of space in the music, and indeed they name Miles Davis' "Bitches Brew" as an influence.

All of the guys play an array of instruments. Robbie's preferred woodwind axe is a bass clarinet, but I might actually like his sax playing better. For good measure, he plays a very mean tabla, and a pandeira (Brazilian tambourine) that has remarkable expressiveness. Chris's percussion setup looks like he went into a percussion store and bought one of everything. He had seven gongs, eleven cymbals, a djembe, another African drum (ashiko, maybe?), a wooden box, a doumbek with a high, crisp sound, and on and on. On one tune, he played a terracotta vase which had a nice bass and a higher, clear sustain. Andy played soprano sax, didjeridoo, flute, and some percussion. He played a kalimba (African alto music box played with your thumbs, more or less) on one very nice tune, "El Jinete". Bruce is the slacker in the instrument count department; he stuck with acoustic and electric pianos, except for one tune he contributed some percussion to.

Most of the tunes on Azure were written by Robbie. Some start with a spacious, slow opening before moving into more up-tempo sections. I really like the bass groove Bruce lays down on the opening track, "Azure". As you'd expect with a group like this, the rhythms are hideously complex in places; one tune is in 11/4 time (named, not coincidentally, "Eleven"), and I couldn't identify the time signatures on a couple. They opened their second set with "Bat Dance", by Chris, in which Robbie and Andy support a long, complex, exciting solo by Chris on the frame drum. The range of sounds ten fingers can get out of a piece of skin stretched across a wide, shallow wooden frame is simply amazing.

Sweet Basil is a great place to hear music. It's new, the food and sound are quite good, and the ventilation keeps the smoke level down. The desserts were excellent, and the potato soup rich. Mayumi had duck and I had lamb for main dishes; they needed a little salt and pepper, but were well prepared and presented. If you're headed there, make reservations, and show up early. Seating is by order of arrival. Tatopani sold out; I would guess the place probably holds 2-300 people. We got there early enough for good, but not great, seats, about 7:00.

The web site only lists last night's gig, but they were talking about a number of other appearances scheduled around Japan in the next several months. Hopefully they'll post a schedule soon. I know Chris is playing a percussion duo concert with, um, I'm having trouble reading the name, Shoko Aratani? at Philia Hall on March 4.

Hmm, Chris and Shoko are also playing with Eitetsu Hayashi on December 23rd? Hayashi is the taiko player of whom another professional musician said, "When Eitetsu plays, times stops and you can hear the Universe breathe." He's astonishing. See this if you can!

Tatopani's CDs can be ordered through their web site, where you'll also find sound samples.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Japanese Gov't to Reward Cybersecurity

The Daily Yomiuri reports today that a tax credit enacted in 2003 will expire at the end of the fiscal year, as originally planned. 10 percent of the purchase price of "IT devices" (from PCs to fax machines; not including software?) is deducted directly directly from corporate tax. In fiscal 2005, companies will save about 510 billion yen (almost five billion U.S. dollars). (I have lots of questions about the aims and success of this measure, especially regarding software, but that's not the point of this posting.)

In its place, the government is considering enacting a package to improve the international competitiveness of companies. One provision may be a similar deduction of "10 percent of the retail price of database management software and other devices aimed at preventing illegal computer access, the use of spyware and information leak among other incidents."

That's a noble but vague goal; I could argue that practically anything was bought to further my cybersecurity. Moreover, security is more about practices than purchases.

I also wonder if companies that create cybersecurity problems a la Sony will have their taxes raised?

In its place, the government is considering enacting a package to improve the international competitiveness of companies. One provision may be a similar deduction of "10 percent of the retail price of database management software and other devices aimed at preventing illegal computer access, the use of spyware and information leak among other incidents."

That's a noble but vague goal; I could argue that practically anything was bought to further my cybersecurity. Moreover, security is more about practices than purchases.

I also wonder if companies that create cybersecurity problems a la Sony will have their taxes raised?

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Shinkansen in China

The Yoimuri Shimbun is reporting today that China will buy sixty Hayate shinkansen (bullet trains) from a consortium of Japanese companies for its planned 12,000km network of high-speed trains. Apparently they will also buy ICE trains from Germany, but not TGV trains from France. No idea how they plan to apportion the different technologies; by region?

Hayate trains currently run at up to 275kph, though JR East is said to be working on speeds up to 360. The Chinese network is proposed to run at 300.

The report says the network will cost more than ten trillion yen (about 80 billion dollars), but doesn't say how many years it will take to do the whole buildout (though some services may start as early as 2008), nor what fraction of that money will be spent on Japanese-made rolling stock. Nikkei says the Hayate trains cost 250 million yen ($2M) per car, and I think those trains are typically ten cars, times sixty trains, that's $1.2 billion dollars.

And in America we have only the Acela, and only in a small area.

Hayate trains currently run at up to 275kph, though JR East is said to be working on speeds up to 360. The Chinese network is proposed to run at 300.

The report says the network will cost more than ten trillion yen (about 80 billion dollars), but doesn't say how many years it will take to do the whole buildout (though some services may start as early as 2008), nor what fraction of that money will be spent on Japanese-made rolling stock. Nikkei says the Hayate trains cost 250 million yen ($2M) per car, and I think those trains are typically ten cars, times sixty trains, that's $1.2 billion dollars.

And in America we have only the Acela, and only in a small area.

How Many Qubits Can Dance on the Head of a Pin?

[Third installment in examining the meaning of scaling a quantum computer. First is here, second one is here. Continued in installment four, here]

I have the cart slightly before the horse in my breadbox posting. In that posting, we were talking about a multi-node quantum computer and its relationship to scalability. But before getting to my quantum multicomputer, we should look at the scalability of a single, large, monolithic machine.

Again, let's consider VLSI-based qubits. In particular, let's look at the superconducting Josephson-junction flux qubit from Dr. Semba's group at NTT (one good paper on it is this one). Their qubit is a loop about 10 microns square. This area is determined by physics, not limited by VLSI feature size; the size of the loop determines the size of the flux quantum, which in turn determines control frequencies, gate speed, and whatnot. (The phase qubit from NIST is more like 100 microns on a side; it's big enough to see!) Semba-san's group is working hard on connecting qubits via an LC oscillator. The paper cited above shows that one qubit couples to the bus; the next step might be two qubits.

So, once they've achieved that, is it good enough? Do they then meet DiVincenzo's criterion for a scalable set of qubits? Let's see. As an engineer, I don't care if the technology scales indefinitely, I care if it scales through regions that solve interesting problems. In this case, we're looking for up to a quarter of a million physical qubits. Can we fit them on a chip? At first glance, it would seem so. Even a small 10mm square chip would fit a million 10-micron square structures. But that ignores I/O pads. Equally important, a glance at the micrograph in the paper above shows that the capacitor is huge compared to the qubit (but you only need one of those per bus that connects a modest-sized group of qubits, and it may be possible to build the capacitor in some more space-efficient manner, or maybe even put it off-chip?). Still more important, these qubits are magnetic, not charge; place them too close together, and they'll interfere. I have no idea what the spacing is (though I assume Semba-san and the others working on this type of qubit have at least thought about this, and may even have published some numbers in a paper I haven't read or don't recall). Control is achieved with a microwave line run past the qubit, so obviously you can't run that too close to other qubits. All of this is a long-winded way of saying there's a lot of physics to be done even before the mundane engineering of floor-planning. We talked a little in the last installment about the need for I/O pads and control lines into/out of the dil fridge. That applies directly to the chip, as well; now we need roughly a pin per qubit, unless a lot more of the signal generators and whatnot can be built directly into our device. Without some pretty major advances in integration, I'll be surprised if you can get more than a thousand qubits into a chip (whether they're charge, spin, flux, what have you). So does that mean we're dead? We can't reach a quarter of a million qubits?

The basic idea of the quantum multicomputer is that we can connect multiple nodes together. We need to create an entangled state that crosses node boundaries, so we need quantum I/O. So, you need the ability to entangle your stationary qubit with something that moves - preferably a photon, though an electron isn't out of the question; a strong laser probe beam may work, too. Then you need a way to get the information out of that photon back into another qubit at the destination node. This is going to be hard, but the alternative is a quantum computer that doesn't extend outside the confines of a single chip. This idea of distributed quantum computing goes back a decade, and there have been some good experiments in this area; I'll post some links references another time.

Bottom line: for the foreseeable future, scalability requires I/O - classical for sure, and maybe quantum. More than a matter of die space for the qubits themselves, I/O pads and lines and space for them on-chip, plus physical interference effects, will drive how many qubits you can fit on a chip. If that number doesn't scale up to the point where it is not the limiting factor in the size of system you can build, then you have to have quantum I/O (some way to entangle on-chip qubits with qubits in another device or another technology).

[Update: Semba-san tells me that the strength of the interaction could be a problem if the qubits are only a micron apart, but at 10um spacing, the interaction drops to order of kHz, low enough not to worry about much.]

I have the cart slightly before the horse in my breadbox posting. In that posting, we were talking about a multi-node quantum computer and its relationship to scalability. But before getting to my quantum multicomputer, we should look at the scalability of a single, large, monolithic machine.

Again, let's consider VLSI-based qubits. In particular, let's look at the superconducting Josephson-junction flux qubit from Dr. Semba's group at NTT (one good paper on it is this one). Their qubit is a loop about 10 microns square. This area is determined by physics, not limited by VLSI feature size; the size of the loop determines the size of the flux quantum, which in turn determines control frequencies, gate speed, and whatnot. (The phase qubit from NIST is more like 100 microns on a side; it's big enough to see!) Semba-san's group is working hard on connecting qubits via an LC oscillator. The paper cited above shows that one qubit couples to the bus; the next step might be two qubits.

So, once they've achieved that, is it good enough? Do they then meet DiVincenzo's criterion for a scalable set of qubits? Let's see. As an engineer, I don't care if the technology scales indefinitely, I care if it scales through regions that solve interesting problems. In this case, we're looking for up to a quarter of a million physical qubits. Can we fit them on a chip? At first glance, it would seem so. Even a small 10mm square chip would fit a million 10-micron square structures. But that ignores I/O pads. Equally important, a glance at the micrograph in the paper above shows that the capacitor is huge compared to the qubit (but you only need one of those per bus that connects a modest-sized group of qubits, and it may be possible to build the capacitor in some more space-efficient manner, or maybe even put it off-chip?). Still more important, these qubits are magnetic, not charge; place them too close together, and they'll interfere. I have no idea what the spacing is (though I assume Semba-san and the others working on this type of qubit have at least thought about this, and may even have published some numbers in a paper I haven't read or don't recall). Control is achieved with a microwave line run past the qubit, so obviously you can't run that too close to other qubits. All of this is a long-winded way of saying there's a lot of physics to be done even before the mundane engineering of floor-planning. We talked a little in the last installment about the need for I/O pads and control lines into/out of the dil fridge. That applies directly to the chip, as well; now we need roughly a pin per qubit, unless a lot more of the signal generators and whatnot can be built directly into our device. Without some pretty major advances in integration, I'll be surprised if you can get more than a thousand qubits into a chip (whether they're charge, spin, flux, what have you). So does that mean we're dead? We can't reach a quarter of a million qubits?

The basic idea of the quantum multicomputer is that we can connect multiple nodes together. We need to create an entangled state that crosses node boundaries, so we need quantum I/O. So, you need the ability to entangle your stationary qubit with something that moves - preferably a photon, though an electron isn't out of the question; a strong laser probe beam may work, too. Then you need a way to get the information out of that photon back into another qubit at the destination node. This is going to be hard, but the alternative is a quantum computer that doesn't extend outside the confines of a single chip. This idea of distributed quantum computing goes back a decade, and there have been some good experiments in this area; I'll post some links references another time.

Bottom line: for the foreseeable future, scalability requires I/O - classical for sure, and maybe quantum. More than a matter of die space for the qubits themselves, I/O pads and lines and space for them on-chip, plus physical interference effects, will drive how many qubits you can fit on a chip. If that number doesn't scale up to the point where it is not the limiting factor in the size of system you can build, then you have to have quantum I/O (some way to entangle on-chip qubits with qubits in another device or another technology).

[Update: Semba-san tells me that the strength of the interaction could be a problem if the qubits are only a micron apart, but at 10um spacing, the interaction drops to order of kHz, low enough not to worry about much.]

Sunday, November 20, 2005

Joint Chip Plant in Japan in 2007?

The Yomiuri Shimbun is reporting that five Japanese semiconductor makers, Hitachi, Toshiba, Matsushita Electric Industrial, NEC Electronics, and Renesas Technology, are planning a 65-nanometer wire width plant. It will be the first time Japanese manufacturers have done a joint chip plant.

Construction is expected to start next year, production in 2007 "at the earliest". Cost might be 200 billion yen (almost two billion U.S. dollars); the share to be paid by each company hasn't been determined yet. The article says it's necessary to keep the companies competitive in the face of "huge capital investments" by South Korean and U.S. manufacturers. I don't think they've picked a location yet.

Construction is expected to start next year, production in 2007 "at the earliest". Cost might be 200 billion yen (almost two billion U.S. dollars); the share to be paid by each company hasn't been determined yet. The article says it's necessary to keep the companies competitive in the face of "huge capital investments" by South Korean and U.S. manufacturers. I don't think they've picked a location yet.

Blogalog: Computer Graphics in Japan?

A pure computer graphics question, the first in a while. I know SIGGRAPH was months ago, but I never got around to asking some of my questions.

Was there any CG art (still or animated) from Japan this year? Who, from what organization? (Got a link?)

Any good technical papers from Japan, or exciting new technology from Japan on the show floor?

I know there are a lot of CG artists in Japan, and I'm not in that circle. It would be fun to get hooked up with them and at least attend the occasional talk or art show.

Was there any CG art (still or animated) from Japan this year? Who, from what organization? (Got a link?)

Any good technical papers from Japan, or exciting new technology from Japan on the show floor?

I know there are a lot of CG artists in Japan, and I'm not in that circle. It would be fun to get hooked up with them and at least attend the occasional talk or art show.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Warp Drive Patented!

Okay, I know I'm blogging a bunch this week, and this seems more like a Friday afternoon thing than a real workday item, but I can't resist this one. Courtesy of Dave Farber's Interesting People list, we have the discovery of a fascinating patent issued by the USPTO on Nov. 1, 2005 to Boris Volfson.

Topic of patent #6,960,975? "Space Vehicle Propelled by the Pressure of Inflationary Vacuum State". A warp drive. Use 10,000 Tesla magnets and a 5meter shell of superconducting material, and you, too, can warp space and time, and travel at "a speed possibly approaching a local light-speed, the local light-speed which may be substantially higher than the light-speed in the ambient space"!

I wonder if this is the first patent for H.G. Wells' cavorite, the anti-gravity material in his novel The First Men in the Moon? (Volfson calls out the comparison directly.)

PDF and HTML versions of the patent available.

Topic of patent #6,960,975? "Space Vehicle Propelled by the Pressure of Inflationary Vacuum State". A warp drive. Use 10,000 Tesla magnets and a 5meter shell of superconducting material, and you, too, can warp space and time, and travel at "a speed possibly approaching a local light-speed, the local light-speed which may be substantially higher than the light-speed in the ambient space"!

I wonder if this is the first patent for H.G. Wells' cavorite, the anti-gravity material in his novel The First Men in the Moon? (Volfson calls out the comparison directly.)

PDF and HTML versions of the patent available.

Congratulations, Yoshi!

Yoshihisa Yamamoto, professor at Stanford and NII and world-renowned expert on quantum optics and various forms of quantum computing technology, received the Medal of Honor with Purple Ribbon yesterday, apparently from the emperor himself. Quite an honor, especially as Yoshi is among the younger recipients.

This is Getting Monotonous...

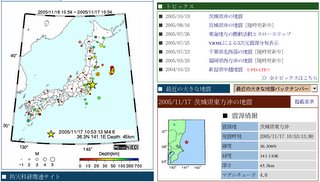

Another 4.8 off the coast of Ibaraki-ken. Figure this time is from Hi-net. The star is the most recent one, the rest are all activity in the last 24 hours. In the right-hand map, we live near the border between the two prefectures in the lower right, almost due north of the easternmost edge of Tokyo Bay. Shaking this time was pretty mild, you definitely wouldn't notice riding in a car or train and might not have even walking.

First Frost in Abiko and W in Kyoto

There's frost on the ground here in Abiko today, and even at 7:30 a.m. Narita Airport is reporting 2C as the temperature. The tree leaves this year are not very pretty, thanks to a sullen but not crisp October. Mikan and the many varieties of mushrooms are in season; I had a Chinese dish for lunch yesterday with maitake, which was a bit surprising. Fall is in full swing.

President Bush is Kyoto, visiting with Prime Minister Koizumi. Laura tried her hand at Japanese calligraphy, and the photo in the paper this morning looks like she caught on quickly.

There was a column in yesterday's Daily Yomiuri by a guy from the Heritage Foundation, who called the state of U.S.-Japan ties the best they've been in fifty years. That's pure spin, but it is true that they're pretty good right now. Bush and Koizumi seem to honestly like each other; their personalities are both swaggering cowboy. Except for beef, trade friction is low. Both are worried about the rise of China, both economically and militarily (environmentally should be a concern, too). Condi and Aso are in Pusan, working on North Korea. We're finishing up a reworking of the security deal. But, most important, Bush and Koizumi need each other. Japan is one of the biggest coalition partners in Iraq. Japan needs U.S. support for the permanent U.N. Security Council seat it so desparately wants.

It's not all smooth; Okinawa has an ambivalent relationship with the U.S. military, and the presence there is getting shuffled. The Okinawa governor took exception to Koizumi's remark that Japan must pay a "certain cost" to enjoy the security brought by the alliance. He correctly interprets that cost as Okinawa continuing to put up with our military.

President Bush is Kyoto, visiting with Prime Minister Koizumi. Laura tried her hand at Japanese calligraphy, and the photo in the paper this morning looks like she caught on quickly.

There was a column in yesterday's Daily Yomiuri by a guy from the Heritage Foundation, who called the state of U.S.-Japan ties the best they've been in fifty years. That's pure spin, but it is true that they're pretty good right now. Bush and Koizumi seem to honestly like each other; their personalities are both swaggering cowboy. Except for beef, trade friction is low. Both are worried about the rise of China, both economically and militarily (environmentally should be a concern, too). Condi and Aso are in Pusan, working on North Korea. We're finishing up a reworking of the security deal. But, most important, Bush and Koizumi need each other. Japan is one of the biggest coalition partners in Iraq. Japan needs U.S. support for the permanent U.N. Security Council seat it so desparately wants.

It's not all smooth; Okinawa has an ambivalent relationship with the U.S. military, and the presence there is getting shuffled. The Okinawa governor took exception to Koizumi's remark that Japan must pay a "certain cost" to enjoy the security brought by the alliance. He correctly interprets that cost as Okinawa continuing to put up with our military.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Magnitude 4.8 Wakeup Call

Am I a prophet, or what? (Mostly what, but I'm working on the prophet thang in case the academic gig falls through.)

At 6:18 this morning, magnitude 4.8 earthquake off the coast of Ibaraki-ken, 40km down. Here in Abiko, it was about shindo 2. Woke me up, sort of (usually I'm up before 6:00, but I worked until 1:00 last night). Not enough to get the adrenalin going, so I just rolled over and went back to sleep. My mother-in-law, who was walking between her house and ours, didn't even feel it.

This is at least the third from the same area and roughly the same size in the last month, and it seems like there has been one about every two weeks since we moved to Abiko in March. As long as it's releasing stress instead of building up, I'm happy.

Monday, November 14, 2005

3D Earthquake Info

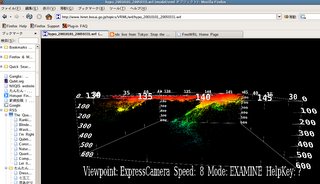

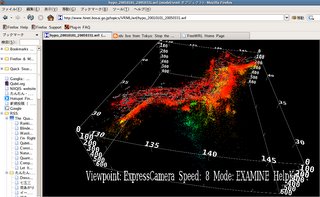

While digging around for the last blog entry, I found a 3D VRML dataset of a year's worth of earthquakes under Japan. A couple of screen shots are above. You can see the subduction zone at the eastern edge of the isles extraordinarily clearly.

I'm using Firefox on Fedora Core 4 Linux. The FreeWRL FC3 RPM installed cleanly and works pretty well for VRML, but doesn't seem to do X3D properly. Be warned, this might take a couple of minutes to load; be patient.

The links:

This is a great use of 3D graphics.

Earthquake Info on Japan

My grandmother, whose ninetieth birthday is coming up soon, watches TV a lot, and calls my mom whenever there's an earthquake reported in Japan.

When there is an earthquake here, I check with tenki.jp, which is the government weather agency's website. Just above and to the right of the map is a pull-down menu of recent quake dates and times. The color-coded dots are the Japanese subjective shaking scale, which goes something like this:

- shindo 1: felt by sensitive people

- shindo 2: felt by many people

- shindo 3: wakeup call!

- shindo 4: pick up items previously precariously perched at higher levels

- shindo 5: call a handyman

- shindo 6: call a contractor

- shindo 7: call the army

Note that, although the numbers are similar, this is not the same as the magnitude of the earthquake; these numbers are what a person feels locally.

That info is filtered and takes a few (6-10) minutes to get posted. Hi-net is the direct access to the seismographic network.

Unfortunately, neither of those seems to have a decent English presence. I like tenki.jp because it has an i-mode interface, so when a quake hits in the middle of the night, I roll over, check my cell phone, then go back to sleep.

It does seem that we are having a lot of magnitude 4.0-5.3-ish quakes lately, mostly just north of us in Ibaraki-ken.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Bigger Than a Breadbox, Smaller than a Football Stadium

[Second in the "practicalities of scalable quantum computers" series. The first installment was Forty Bucks a Qubit. Third is How Many Qubits Can Dance on the Head of a Pin?]

After talking to various people, I'm raising the target price on my quantum computer to a hundred million dollars. The U.S. government clearly spends that much on cluster supercomputers, though I don't think that they reached that level in the heyday of vector machines. BlueGene, for example, built by IBM, has 131,072 processors (65536 dual-core), and there's no way you're going to build a system like that, counting packaging, power, memory, storage, and networking, for less than a grand a processor (all these prices are ignoring physical plant, including the building).

Let's talk about packaging, cooling, and housing a semiconductor-based quantum computer. Even though we're talking about manipulating individual quanta, the space, power, thermal, and helium budgets for this are large. Helium? Yeah, helium. Both superconducting qubits and quantum dot qubits are operated at millikelvin temperatures, and the way you get there is by using a dilution refrigerator.

A dilution refrigerator, or dil fridge, uses the different condensation characteristics of helium-3 and helium-4 to cool things down to millikelvin temperatures. See the web pages here, here, and here, and the excellent PDF of the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Dilution Refrigerator from Charlie Marcus' lab at Harvard. All of the dil fridges I have ever seen are from Oxford Instruments.

Although there are a bunch of models, all the ones I've seen are almost two meters tall and a little under a meter in diameter, and you load your test sample in from the top on a long insert, so you need another two meters' clearance above (plus a small winch). A dil fridge is limited in theory to something like 7 millikelvin, and in practice to higher values depending on model. They can typically extract only a few hundred microwatts of heat from the device under test, which is limited to a few cubic centimeters. You're also going to need lots of clearance around the fridge, for operators, rack-mount equipment, and space to move equipment down the aisles. All this is by way of saying that you need quite a bit of space, power, and money for each setup. Let's call such a setup a "pod".

I'm considering the design of a quantum multicomputer, a set of quantum computing nodes interconnected via a quantum network. Let's start with one node per pod, and again set our target at a machine for factoring a 1,024-bit number. If we put, say, five application-level qubits per node, and add two levels of Steane [[7,1,3]] code, we've got 250 physical qubits per node, and 1,024 nodes in 1,024 pods. If each pod requires an area three meters square, we need an area about 100 meters by 100 meters for our total machine (bigger than a football field, smaller than a football stadium).

The thermal engineering is a serious problem. The electronics for each qubit currently fill a 19-inch rack, but a lot of that is measurement, not control, and of course in a production-engineered system we can increase the integration. It's still going to be a lot of equipmentfor 250 qubits, and worse, a lot more heat. It seems unlikely that our thermal budget will allow us to put the control electronics in the dil fridge (and some of it may not operate properly at such low temperatures, anyway). So, we're going to have to control it from outside. That means lots of signal lines - one per qubit for control, plus quite a few more (maybe as many as one per qubit) for measurement and various other things. Probably 4-500 microcoaxes that have to reach inside the fridge, each one carrying heat with it. Yow. Unless you substantially raise the extraction rate of the dil fridge, each line and measurement device is limited to about a microwatt - plus the heat that will leak through the fridge body itself. In the end it's almost certainly a multi-stage system, with parts running at room temperature, parts at liquid helium temps, and only the minimum necessary in the dil fridge itself.

Finally, we have to think about money again. We've just set a limit of about $100K per pod. I've never priced dil fridges, but I'd be surprised if they're cheaper than that (I wonder what kind of volume discount you get when you offer to buy a thousand dil fridges...), and we have a bunch of electronics and whatnot to pay for, in addition to the quantum computing device itself! We can do better on floor space and money if we can fit more than one node per pod, but doubling or quadrupling the number of coaxes and the heat budget is a daunting proposition on an already extremely aggressive engineering challenge.

It's not that I think this linear extrapolation from our current state is necessarily the way production systems will really be built (it's also worth noting that NMR, ion trap, optical lattice, and atom chip systems would require a completely different analysis). I'm trying to create a rough idea of the constraints we face and the problems that must be solved. One thing's for sure, though: when I found my quantum computing startup, world-class thermal and packaging engineers will be just as high on my shopping list as the actual quantum physicists.

After talking to various people, I'm raising the target price on my quantum computer to a hundred million dollars. The U.S. government clearly spends that much on cluster supercomputers, though I don't think that they reached that level in the heyday of vector machines. BlueGene, for example, built by IBM, has 131,072 processors (65536 dual-core), and there's no way you're going to build a system like that, counting packaging, power, memory, storage, and networking, for less than a grand a processor (all these prices are ignoring physical plant, including the building).

Let's talk about packaging, cooling, and housing a semiconductor-based quantum computer. Even though we're talking about manipulating individual quanta, the space, power, thermal, and helium budgets for this are large. Helium? Yeah, helium. Both superconducting qubits and quantum dot qubits are operated at millikelvin temperatures, and the way you get there is by using a dilution refrigerator.

A dilution refrigerator, or dil fridge, uses the different condensation characteristics of helium-3 and helium-4 to cool things down to millikelvin temperatures. See the web pages here, here, and here, and the excellent PDF of the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Dilution Refrigerator from Charlie Marcus' lab at Harvard. All of the dil fridges I have ever seen are from Oxford Instruments.

Although there are a bunch of models, all the ones I've seen are almost two meters tall and a little under a meter in diameter, and you load your test sample in from the top on a long insert, so you need another two meters' clearance above (plus a small winch). A dil fridge is limited in theory to something like 7 millikelvin, and in practice to higher values depending on model. They can typically extract only a few hundred microwatts of heat from the device under test, which is limited to a few cubic centimeters. You're also going to need lots of clearance around the fridge, for operators, rack-mount equipment, and space to move equipment down the aisles. All this is by way of saying that you need quite a bit of space, power, and money for each setup. Let's call such a setup a "pod".

I'm considering the design of a quantum multicomputer, a set of quantum computing nodes interconnected via a quantum network. Let's start with one node per pod, and again set our target at a machine for factoring a 1,024-bit number. If we put, say, five application-level qubits per node, and add two levels of Steane [[7,1,3]] code, we've got 250 physical qubits per node, and 1,024 nodes in 1,024 pods. If each pod requires an area three meters square, we need an area about 100 meters by 100 meters for our total machine (bigger than a football field, smaller than a football stadium).

The thermal engineering is a serious problem. The electronics for each qubit currently fill a 19-inch rack, but a lot of that is measurement, not control, and of course in a production-engineered system we can increase the integration. It's still going to be a lot of equipmentfor 250 qubits, and worse, a lot more heat. It seems unlikely that our thermal budget will allow us to put the control electronics in the dil fridge (and some of it may not operate properly at such low temperatures, anyway). So, we're going to have to control it from outside. That means lots of signal lines - one per qubit for control, plus quite a few more (maybe as many as one per qubit) for measurement and various other things. Probably 4-500 microcoaxes that have to reach inside the fridge, each one carrying heat with it. Yow. Unless you substantially raise the extraction rate of the dil fridge, each line and measurement device is limited to about a microwatt - plus the heat that will leak through the fridge body itself. In the end it's almost certainly a multi-stage system, with parts running at room temperature, parts at liquid helium temps, and only the minimum necessary in the dil fridge itself.

Finally, we have to think about money again. We've just set a limit of about $100K per pod. I've never priced dil fridges, but I'd be surprised if they're cheaper than that (I wonder what kind of volume discount you get when you offer to buy a thousand dil fridges...), and we have a bunch of electronics and whatnot to pay for, in addition to the quantum computing device itself! We can do better on floor space and money if we can fit more than one node per pod, but doubling or quadrupling the number of coaxes and the heat budget is a daunting proposition on an already extremely aggressive engineering challenge.

It's not that I think this linear extrapolation from our current state is necessarily the way production systems will really be built (it's also worth noting that NMR, ion trap, optical lattice, and atom chip systems would require a completely different analysis). I'm trying to create a rough idea of the constraints we face and the problems that must be solved. One thing's for sure, though: when I found my quantum computing startup, world-class thermal and packaging engineers will be just as high on my shopping list as the actual quantum physicists.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

NEC's Quantum Telephone

This posting is offline for the moment. Please send me email if you have questions or concerns.

[I have other postings on QKD at Stop the Myth and More on the Myth.]

[I have other postings on QKD at Stop the Myth and More on the Myth.]

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Forty Bucks a Qubit

First in a series of thoughts on what it means to build a scalable quantum computer... [Second installment is Bigger Than a Breadbox, Smaller Than a Football Stadium.]

My guess on the price at which the first production quantum computer is sold: forty bucks a qubit. Of course, the definition of "production" is fuzzy, but I mean a machine that is bought and installed for the purpose of solving real problems, not just a "let's support research" buy from the U.S. government. That is, it has to solve a problem that there's not a comparable classical solution for.

This guess is based on the assumption that the machine will be built to run Shor's factoring algorithm on a 1,024-bit number, which is sort of a questionable assumption, but we'll go with it (some physicists want them for direct simulation of complex Hamiltonians, but I don't understand that well enough to make any predictions there at all). That takes about five kilobits of application-level qubit space, and we'll multiply by fifty to support two levels of QEC. The [[7,1,3]] Steane code twice would be 49, but codes in production use are likely to be somewhat more efficient (maybe as good as 3:1, but I doubt much better), but there will no doubt be a need for additional space I didn't account for above, so we'll guess a quarter of a million physical qubits.

If you assume ten million U.S. dollars is a reasonable price for a machine with unique capabilities, that gives you forty bucks a qubit. I could easily be off by an order of magnitude in either direction, but I'll be very surprised if it's over a thousand dollars or under a buck.

Anyway, that's my prediction. What do you think? High? Low?

Next questions: what technology, and when?

I should put up a prediction at LongBets.org...

My guess on the price at which the first production quantum computer is sold: forty bucks a qubit. Of course, the definition of "production" is fuzzy, but I mean a machine that is bought and installed for the purpose of solving real problems, not just a "let's support research" buy from the U.S. government. That is, it has to solve a problem that there's not a comparable classical solution for.

This guess is based on the assumption that the machine will be built to run Shor's factoring algorithm on a 1,024-bit number, which is sort of a questionable assumption, but we'll go with it (some physicists want them for direct simulation of complex Hamiltonians, but I don't understand that well enough to make any predictions there at all). That takes about five kilobits of application-level qubit space, and we'll multiply by fifty to support two levels of QEC. The [[7,1,3]] Steane code twice would be 49, but codes in production use are likely to be somewhat more efficient (maybe as good as 3:1, but I doubt much better), but there will no doubt be a need for additional space I didn't account for above, so we'll guess a quarter of a million physical qubits.

If you assume ten million U.S. dollars is a reasonable price for a machine with unique capabilities, that gives you forty bucks a qubit. I could easily be off by an order of magnitude in either direction, but I'll be very surprised if it's over a thousand dollars or under a buck.

Anyway, that's my prediction. What do you think? High? Low?

Next questions: what technology, and when?

I should put up a prediction at LongBets.org...

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Linux on a Vaio: CPU speed scaling

If you're looking for Fedora Core 6 (FC6) help, I've added a note here. (2006/11/7)

Random technical note for surfers looking for help...

[Request: this page gets a fair number of hits, but I'm not getting any feedback on it. If it doesn't have enough information to be useful to you, drop me a comment and let me know how I can make it better!]

I'm running Fedora Core 4 on a Sony Vaio type T laptop. One thing I never had working was CPU frequency scaling. One symptom was "error: no such device" during boot. If I tried it by hand, I got

My *guess* (not having read the code) is that the kernel dynamically attempts to figure out what your hardware is, and load the right kernel module. In my case, it was picking acpi-cpufreq, which is wrong, and so it was putting out a misleading error message. If it gets it right, I don't think you need a specific configuration step. If it can't figure it out, though, you need to add the "DRIVER=" line

to /etc/cpuspeed.conf. Here's my config, for a 900MHz Celeron M, which is apparently similar to a P4:

Once I did that, it all works well. Copy the above, and try uncommenting the different "DRIVER" lines until you find one that works.

/proc/acpi/processor/CPU0/throttling doesn't appear to correctly flag the current CPU speed, but there is lots of info in /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/ that wasn't present before this module loaded correctly, such as

I added the CPU frequency monitor to my GNOME panel, and I see it scaling from 900MHz down to 112MHz pretty aggressively as the machine goes idle. I can't manually adjust the speed from that widget, like some people can, but I think that's because my monitor isn't running setuid.

My minimum power consumption now seems to be about 9.4 watts with the WLAN off, disk idle, CPU speed down, and screen brightness on minimum. That should be good enough for 5.5 hours, not too far off Sony's claim of 6 hours of battery life. Realistically, I was getting 4-4.5 before this change with mid-level screen brightness, we'll see if the CPU frquency scaling actually brings me benefits or not...

The one thing I'm still missing is that it comes out of sleep only slowly, and not very reliably.

Hope this helps someone.

Random technical note for surfers looking for help...

[Request: this page gets a fair number of hits, but I'm not getting any feedback on it. If it doesn't have enough information to be useful to you, drop me a comment and let me know how I can make it better!]

I'm running Fedora Core 4 on a Sony Vaio type T laptop. One thing I never had working was CPU frequency scaling. One symptom was "error: no such device" during boot. If I tried it by hand, I got

[root@pokhara sony_acpi]# pushd /lib/modules/2.6.13-1.1526_FC4/kernel/arch/i386/kernel/cpu/cpufreq/

/lib/modules/2.6.13-1.1526_FC4/kernel/arch/i386/kernel/cpu/cpufreq /home/rdv/linux/sony_acpi

[root@pokhara cpufreq]# ls

acpi-cpufreq.ko p4-clockmod.ko powernow-k8.ko speedstep-smi.ko

[root@pokhara cpufreq]# insmod acpi-cpufreq.ko

insmod: error inserting 'acpi-cpufreq.ko': -1 No such device

[root@pokhara cpufreq]#

My *guess* (not having read the code) is that the kernel dynamically attempts to figure out what your hardware is, and load the right kernel module. In my case, it was picking acpi-cpufreq, which is wrong, and so it was putting out a misleading error message. If it gets it right, I don't think you need a specific configuration step. If it can't figure it out, though, you need to add the "DRIVER=" line

to /etc/cpuspeed.conf. Here's my config, for a 900MHz Celeron M, which is apparently similar to a P4:

[rdv@pokhara dist-arch]$ cat /etc/cpuspeed.conf

VMAJOR=1

VMINOR=1

# uncomment this and set to the name of your CPUFreq module

#DRIVER="powernow-k7"

#DRIVER="acpi-cpufreq"

#DRIVER="powernow-k8"

#DRIVER="speedstep-smi"

DRIVER="p4-clockmod"

# Let background (nice) processes speed up the cpu

OPTS="$OPTS -n"

# Add your favorite options here

#OPTS="$OPTS -s 0 -i 10 -r"

# uncomment and modify this to check the state of the AC adapter

#OPTS="$OPTS -a /proc/acpi/ac_adapter/*/state"

# uncomment and modify this to check the system temperature

#OPTS="$OPTS -t /proc/acpi/thermal_zone/*/temperature 75"

Once I did that, it all works well. Copy the above, and try uncommenting the different "DRIVER" lines until you find one that works.

/proc/acpi/processor/CPU0/throttling doesn't appear to correctly flag the current CPU speed, but there is lots of info in /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/ that wasn't present before this module loaded correctly, such as

[rdv@pokhara dist-arch]$ cat /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_available_frequencies

112500 225000 337500 450000 562500 675000 787500 900000

I added the CPU frequency monitor to my GNOME panel, and I see it scaling from 900MHz down to 112MHz pretty aggressively as the machine goes idle. I can't manually adjust the speed from that widget, like some people can, but I think that's because my monitor isn't running setuid.

My minimum power consumption now seems to be about 9.4 watts with the WLAN off, disk idle, CPU speed down, and screen brightness on minimum. That should be good enough for 5.5 hours, not too far off Sony's claim of 6 hours of battery life. Realistically, I was getting 4-4.5 before this change with mid-level screen brightness, we'll see if the CPU frquency scaling actually brings me benefits or not...

The one thing I'm still missing is that it comes out of sleep only slowly, and not very reliably.

Hope this helps someone.

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Of Empresses, Shrines, Marines, and Universities: Japanese Politics

There has been a bunch of news lately, so I feel compelled to stick in just a short summary. Not a lot of commentary...

The U.S. and Japan are in the midst of reworking much of the bilateral security agreement. This may not make news in the U.S., but it's front page of the papers here every day for the last week or so. A few marines will move to Guam, one major Okinawa base will expand, and a lot of bases around Japan will shuffle. Okinawa is poor and very dependent on the U.S. armed forces for its economy, but friction over aircraft noise, accidents, barfights and rapes are constant. If memory serves, we have 40,000 armed forces personnel stationed here. America basically never withdraws from a country once we've settled in; we have bases in more than 100 countries around the world. In conjunction with the shuffle, Japan has agreed that a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier can be stationed at Yokosuka (south of Tokyo). Although a significant fraction of Japan's electricity is nuclear-generated, they have long objected to a nuclear-powered American ship here, but the Kitty Hawk, America's last non-nuclear aircraft carrier, is due to be retired soon. I think this is a proxy fight for whether or not the U.S. armed forces are allowed to have nuclear weapons on Japanese soil, which, as far as I can tell, is handled on a "don't ask, don't tell" basis.

Speaking of things war, the Yomiuri Shimbun recently commissioned a poll on responsibility for WWII. 67 percent said leaders of the Imperial Japanese Army or Navy followed by prime ministers (33), politicians (27), and Emperor Hirohito (19) (respondents were allowed to pick more than one answer). More interestingly, only 34 percent said that the wars against China and the U.S. were wars of aggression. The English-language Daily Yomiuri doesn't give the exact question or what the rest of the respondents thought, but that's an uncomfortably low number. Only 25 percent said their primary knowledge of WWII is through school; 34 percent said relatives (and the number of people with direct experience of the war is naturally declining rapidly). It's often said that the victors write the history, but in Japan, the losers got to write (or, in the case of schoolbooks, ignore) a big chunk of it, and nationalist politicians and right-wing organizations are still common.

The courts have issued a mixed bag of rulings recently on whether or not Prime Minister Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni Jinja, where 14 class-A war criminals and numerous minor ones are enshrined, violate the constitution's separation of church and state. At first glance, it seems odd; Bush led a prayer service after 9/11, after all. But this is really another proxy fight over opinions, contrition and responsibility for the war. China and South Korea get offended every time he goes, but in China's case, at least, it seems to be at least partially a calculated political attempt to keep their own people annoyed at the Japanese. Shinzo Abe, one of the candidates to succeed Koizumi next year when he steps down, has said he would continue the practice.

Koizumi shuffled his cabinet yesterday. Some of the current cabinet members have shifted political parties as many as five times in the last fifteen years; here parties seem to be much more about political fortunes and factions than about actual policy differences, with the exceptions of the minor communist and socialist parties. There are eighteen cabinet ministers, counting Koizumi, two of whom are women. There are profiles in today's paper, not complete but a few interesting facts. At least three seem to be sons or grandsons of former ministers, and two are former university professors. A breakdown of universities:

The cabinet includes a "state minister in charge of measures for declining birthrate and gender equality" (Inoguchi); I think the last two holders of this post have been women, though I'm unclear on how long it has been a cabinet post and whether it's a "woman's seat". There are two posts that seem to have some science and technology responsibility, "state minister for science, technology and IT policy" (Matsuda), and "education, science and technology minister" (Kosaka); I'm unclear on how responsibilities are divided up.

Speaking of women, the government is considering rewriting the laws governing imperial succession. At the moment, only a man can be emperor, but the current crown prince has only a daughter (Aiko, who is two). There is practically an Aiko cult here; the imperial family's privacy is guarded jealously, and when a short video of Aiko playing was released last winter, there were TV shows devoted to finding the manufacturers of the toys she was seen playing with. The debate is over whether succession should be oldest child, or whether a younger brother should take precedence over an older sister, or even if the emperor's younger brother should take precedence over the emperor's daughters. Japan has had women emperors, but not in many centuries.

Finally, the constitution here is being rewritten. The Liberal Democratic Party is trying to clarify the language around Japan's Self Defense Forces, allowing them to use force in international peacekeeping operations and even in defense of an ally (if you don't know, Japan's constitution currently renounces war as a right of the state in its famous "Article 9", which has always made the existence of the JSDF political ambiguous). The LDP will likely slip in some language designed to make Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni acceptable, too.

Anyway, interesting goings on here that can impact the entire international scene, but since many of them are policy wonk-ish issues, they probably aren't getting a lot of press elsewhere.

The U.S. and Japan are in the midst of reworking much of the bilateral security agreement. This may not make news in the U.S., but it's front page of the papers here every day for the last week or so. A few marines will move to Guam, one major Okinawa base will expand, and a lot of bases around Japan will shuffle. Okinawa is poor and very dependent on the U.S. armed forces for its economy, but friction over aircraft noise, accidents, barfights and rapes are constant. If memory serves, we have 40,000 armed forces personnel stationed here. America basically never withdraws from a country once we've settled in; we have bases in more than 100 countries around the world. In conjunction with the shuffle, Japan has agreed that a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier can be stationed at Yokosuka (south of Tokyo). Although a significant fraction of Japan's electricity is nuclear-generated, they have long objected to a nuclear-powered American ship here, but the Kitty Hawk, America's last non-nuclear aircraft carrier, is due to be retired soon. I think this is a proxy fight for whether or not the U.S. armed forces are allowed to have nuclear weapons on Japanese soil, which, as far as I can tell, is handled on a "don't ask, don't tell" basis.

Speaking of things war, the Yomiuri Shimbun recently commissioned a poll on responsibility for WWII. 67 percent said leaders of the Imperial Japanese Army or Navy followed by prime ministers (33), politicians (27), and Emperor Hirohito (19) (respondents were allowed to pick more than one answer). More interestingly, only 34 percent said that the wars against China and the U.S. were wars of aggression. The English-language Daily Yomiuri doesn't give the exact question or what the rest of the respondents thought, but that's an uncomfortably low number. Only 25 percent said their primary knowledge of WWII is through school; 34 percent said relatives (and the number of people with direct experience of the war is naturally declining rapidly). It's often said that the victors write the history, but in Japan, the losers got to write (or, in the case of schoolbooks, ignore) a big chunk of it, and nationalist politicians and right-wing organizations are still common.

The courts have issued a mixed bag of rulings recently on whether or not Prime Minister Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni Jinja, where 14 class-A war criminals and numerous minor ones are enshrined, violate the constitution's separation of church and state. At first glance, it seems odd; Bush led a prayer service after 9/11, after all. But this is really another proxy fight over opinions, contrition and responsibility for the war. China and South Korea get offended every time he goes, but in China's case, at least, it seems to be at least partially a calculated political attempt to keep their own people annoyed at the Japanese. Shinzo Abe, one of the candidates to succeed Koizumi next year when he steps down, has said he would continue the practice.

Koizumi shuffled his cabinet yesterday. Some of the current cabinet members have shifted political parties as many as five times in the last fifteen years; here parties seem to be much more about political fortunes and factions than about actual policy differences, with the exceptions of the minor communist and socialist parties. There are eighteen cabinet ministers, counting Koizumi, two of whom are women. There are profiles in today's paper, not complete but a few interesting facts. At least three seem to be sons or grandsons of former ministers, and two are former university professors. A breakdown of universities:

- Keio U.: 4 (Koizumi himself, Takenaka, Kosaka, Kawasaki)

- Tokyo U.: 3 (Chuma, Kutsukake, Yosano)

- Gakushuin U., "studied at Stanford and London School of Economics": 1 (Aso)

- Chuo U.: 1 (Nikai)

- Cairo U. (Egypt): 1 (Koike)

- Yale U. Ph.D. (U.S.) (undergrad unstated): 1 (Inoguchi)

- unstated: 7

The cabinet includes a "state minister in charge of measures for declining birthrate and gender equality" (Inoguchi); I think the last two holders of this post have been women, though I'm unclear on how long it has been a cabinet post and whether it's a "woman's seat". There are two posts that seem to have some science and technology responsibility, "state minister for science, technology and IT policy" (Matsuda), and "education, science and technology minister" (Kosaka); I'm unclear on how responsibilities are divided up.

Speaking of women, the government is considering rewriting the laws governing imperial succession. At the moment, only a man can be emperor, but the current crown prince has only a daughter (Aiko, who is two). There is practically an Aiko cult here; the imperial family's privacy is guarded jealously, and when a short video of Aiko playing was released last winter, there were TV shows devoted to finding the manufacturers of the toys she was seen playing with. The debate is over whether succession should be oldest child, or whether a younger brother should take precedence over an older sister, or even if the emperor's younger brother should take precedence over the emperor's daughters. Japan has had women emperors, but not in many centuries.

Finally, the constitution here is being rewritten. The Liberal Democratic Party is trying to clarify the language around Japan's Self Defense Forces, allowing them to use force in international peacekeeping operations and even in defense of an ally (if you don't know, Japan's constitution currently renounces war as a right of the state in its famous "Article 9", which has always made the existence of the JSDF political ambiguous). The LDP will likely slip in some language designed to make Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni acceptable, too.

Anyway, interesting goings on here that can impact the entire international scene, but since many of them are policy wonk-ish issues, they probably aren't getting a lot of press elsewhere.